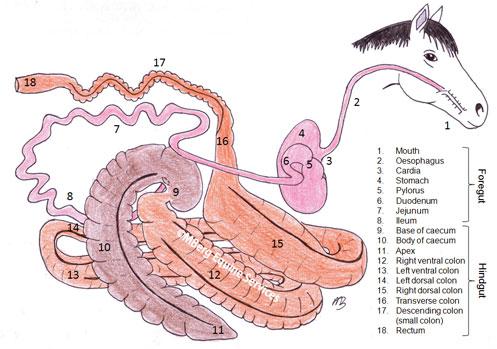

The caecum and colon of the horse are responsible for reabsorbing fluid (up to 100L daily) that is secreted into the foregut of the horse. Diarrhoea in the horse is therefore almost always attributable to malfunction of the caecum and colon.

Colitis is the term applied to any horse with acute onset of watery diarrhoea. The condition may be mild, with a slight change in consistency of manure all that is noted. However, severe colitis may be accompanied by the following signs:

- Acute fever and watery diarrhoea with or without blood

- Rectal straining, abdominal pain and passage of blood in faeces

- With extensive damage to the lining of the gut and loss of protein, ventral/limb/organ oedema (swelling) can develop

- Necrosis (death) of colon can lead to marked changes in peritoneal fluid (increased white cell count, red cell count and total protein level). A raised blood concentration of ALP may indicate extensive damage to the wall of the colon.

Complications associated with colitis include thrombophlebitis of the veins (due to hypercoagulability), laminitis, colon infarction (loss of blood supply) and, rarely, Aspergillus pneumonia. The most peracute cases of severe, febrile diarrhoea in adult horses can lead to death within hours of showing signs, or even before signs of diarrhoea eventuate.

Causes of Acute Pyrexic Diarrhoea in Adult Horses

- Endotoxaemia

- Endotoxins are found in the cell wall of gram negative bacteria. They are normally present in large amounts in the intestinal contents, but are prevented from entering the systemic circulation by gastrointestinal defence mechanisms. If these natural defence mechanisms are compromised through damage to the lining of the gut, endotoxins can enter the circulation leading to fever and diarrhoea. Such situations may arise where there is a restricted blood supply (e.g. due to Strongylus infection), invasion by pathological bacteria, parasites, inflammatory cells and the presence of irritants or toxins. Grain engorgement and gram negative sepsis are two other mechanisms by which endotoxaemia may result.

- Treatment includes low dose flunixin, supportive fluid therapy, intestinal adsorbents (e.g. biosponge) and correction of any underlying sepsis or intestinal lesion.

- Salmonella

- Salmonella causes an enterocolitis by invading and destroying the lining of the gut, leaving a reduced area for fluid absorption and causing protein leakage. Salmonella also produces an enterotoxin. It can cause septicaemia in foals, though only rarely in adults. The normal flora of the equine gut is hostile to Salmonella survival, however if there is a pre-existing disturbance to the flora of the gut the infective dose of Salmonella is much lower. Animals become predisposed to infection by exhaustion, dietary changes, weaning, pregnancy, adverse weather, transport, general anaesthetic, surgery and antibiotic therapy.

- Fever, inappetence and moderate abdominal pain may precede diarrhoea by 2-4 days. Mucus membranes may be injected (darker, more intense in colour), white cells are generally low. Diarrhoea is projectile and foul smelling.

- Diagnosis is based on a positive faecal culture, however it is notoriously difficult to obtain and five negative samples are required before Salmonella can be ruled out as a cause. Salmonella is a notifiable disease.

- Treatment consists of fluid support and symptomatic treatment. Antibiotics frequently do not alter the course of the diarrhoea and are not generally recommended in adult horses. In foals, as septicaemia frequently accompanies the diarrhoea, gram negative antibiotics are essential.

- Clostridium perfringens

- Not all strains produce disease and Clostridium perfringens can be cultured from the manure of clinically healthy horses. Colitis is caused by strains that produce the beta-2 toxin, and production only occurs under certain environmental conditions. Use of certain antibiotics has been associated with toxin production.

- Treatment includes fluid support and symptomatic therapy. Metronidazole may have a place in treatment of typhlocolitis caused by C. perfringens.

- Antibiotic induced diarrhoea

- Severe, often fatal diarrhoea can be induced in adult horses through the administration of multiple different antibiotics in an attempt to control an unresponsive, usually unidentified infection. Ceasing all antibiotics together with symptomatic treatment is recommended.

- Mass Emergence of hyopbiotic (‘dormant’) cyathostomes or an acute parasite burden

- This tends to occur more commonly in late winter to early spring and individuals are often well wormed, with zero faecal egg count and may be the only one affected in a herd with identical management. Worming in some instances may initiate the emergence. Diagnosis should be suspected with cyathostome larvae are seen on the rectal glove after examination.

- Potomac Fever (not in Australia)

- Arsenic Toxicity (and other heavy metals)

- Organophosphate Toxicity

Causes of Chronic Diarrhoea in Adult Horses

- Mature parasite burdens

- Suspected on the basis of poor worming history (or known parasite resistance in the area) and easily diagnosed by high faecal egg counts. Rule out before other causes are considered.

- Chronic Equine Diarrhoea

- Horses are usually bright with normal clinical signs and blood results. They may have a reasonable appetite but fail to maintain peak condition and performance. Occasionally electrolyte depletion may result in lethargy.

- Extensive faecal water loss is assumed to be due to the disturbed fermentation occurring in the large colon. A faecal pH less than 6.8 may support a finding of abnormal fermentation.

- Many treatments have been tried, but none is successful to the exclusion of others. Diarrhoea may persist despite all treatment but will invariably spontaneously resolve with time (up to 12 months).

- Assess the diet. Diets high in grain or lush young grass will cause soft unformed faeces. Altering the diet to contain more mature fibre may be all that is necessary. Founderguard or Equisure may assist in raising pH levels in the gut. Probiotics may be beneficial e.g. yoghurt or commercial preparations. Slowing intestinal transit with Buscopan is another treatment option sometimes used.

- Peritonitis

- Frequently seen in association with signs of fever, low grade abdominal pain, lethargy and reluctance to move, but also may be seen with diarrhoea. Diarrhoea is usually only associated with severe, secondary peritonitis which has a guarded prognosis i.e. not the more common Actinobacillus peritonitis which responds well to antibiotic therapy and has a good prognosis.

- Diagnosis is by peritoneal tap, turbid peritoneal fluid with a high white cell count being diagnostic. Increased peritoneal fluid lactate that is high, low peritoneal fluid glucose and bacteria seen on a smear of peritoneal fluid sediment are also diagnostic.

- Treatment involves attending to the underlying primary cause. Broad spectrum antibiotic cover and measure to prevent intestinal adhesion formation are recommended.

- Hypobiotic Cyathostome Burdens

- Immature cyathostome larvae sometimes encyst in the caecal and colonic mucosa rather than completing their life cycle. In this form, they are not susceptible to most drugs. Hypobiotic larvae cause 2 different clinical syndromes: a gradual progressive protein losing chronic diarrhoea or an acute onset watery diarrhoea associated with mass emergence of larvae.

- Some cases have been confirmed by rectal biopsy. Affected horses are seen most commonly in winter and early spring. They have frequently been well wormed and have a zero faecal egg count. Single horses may be affected in a group of horses sharing identical management and parasite exposure.

- Preferred treatment is with moxidectin. Fenbendazole can be used over a 5 day period, however the inflammatory response created around the dead parasite using this treatment may be worse than the initial problem. Symptomatic treatment may be indicated if the diarrhoea is severe e.g. codeine or morphine. Cortisone should be considered if the protein loss is severe and bacterial causes of disease have been ruled out or considered unlikely. Broad spectrum antibiotic cover may be warranted if extensive colon damage is suspected.

- Infiltrative Bowel Diseases

- All are associated with marked protein loss into the gut. They can occur in the large intestine causing diarrhoea or the small intestine, giving rise to malabsorption.

- Inflammatory bowel diseases are all of unknown origin and may involve immune suppression. Recurrent night fevers are sometimes noted.

- Lymphoma is one of the most common equine malignancies. They can occur in young horses as well as old. Often the only lab finding is a non-specific elevation in fibrinogen. Occasionally calcium may be increased.

- Sand

- If ingested in sufficient quantity, sand may produce signs of low grade colic and/or intermittent chronic diarrhoea. Sand can be demonstrated in the manure – mix the manure in a bucket with water and notice any sand settling out. As sand accumulates in the large colon and caecum, auscultation of the abdomen in this region with a stethoscope may result in a ‘waves on the beach’ sound. Sand may also be seen on ultrasound evaluation.

- Treatment with psyllium husk orally for 5 days each month is traditionally considered one of the most successful ways of removing sand. If the colon is completely obstructed by sand i.e. impacted, then psyllium is not recommended. In this instance, withholding feed and repeatedly tubing the horse with water/electrolytes is indicated to break down the sand mass.

- Toxic, Irritant or Corrosive Compounds

- May result in inflammatory or erosive bowel lesions that lead to diarrhoea. Toxic doses of phenylbutazone may cause a right dorsal colitis. At safe, prescribed dose rates, phenylbutazone is a valid anti-inflammatory medication.

- Food Allergy

- Skin wheals or other concurrent signs of an allergic response would support this diagnosis. Test results are often non-specific. Food trials involving withholding the offending food are easy to carry out and may help identify the offending substance.